On Lineage

Yellow Trauma: The Possibility of a New Aesthetic

Life like still

Yellow and silenced

Like the Cymbidium

In ogle

Like the petals

Thin and weightless

Lifeless edges

Prolonged and half- lived

Mornings rehearsed

in the moan of the unheard

The emotional labour unpaid

Reckoned to be free and to be bees

Drained branches of trees

These strained bees in thralldom

Unrehearsed freedom

Nectar

Life like nectar

The Covid-19 pandemic was a moment of fragility, loss, flux and change that impacted not only society but also individuals, unexpectedly altering their experiences of lineage and genealogy. The brutality of hate crimes against Asians was witnessed across the world during that time. The virus repeatedly evoked the Modernist discourse of the Yellow Peril; a refashioning of the Western imagination of the East and the cultural Other. It was not the first time collective memories of colonialism were recalled for Asians.

Yellow Trauma delineates the contemporary experience of being Asian in the current world through the languages of the audio, visual and text.

In contrast to the event-based model of trauma, which was developed referring to events in the Euro-American histories, e.g., the Holocaust, Yellow Trauma espouses a model of the everyday impacts of racism, sexism, homophobia, ablism and classism etc., that are recognised as complex post-traumatic stress disorder, insidious trauma or oppression-based trauma. The hegemonic, event-based conception of trauma is innately a Euro-America-centric monoculture-oriented definition, which hinders recognition and understanding of the long-term cumulative effects of day-to-day experiences of racism and institutional oppression.

Likewise, the establishment of trauma theories and aesthetics in the early 1990s strongly relied on Holocaust testimonies and films, which have contributed to the centring of the Holocaust as the founding human experience for trauma. Cultural trauma theorists such as Cathy Caruth discovered the unknowability and irrepresentability of trauma within the framework of trauma as history. Trauma theory developed as a subfield of memory studies. The narrow canon of trauma aesthetics is constrained within the Modernists’ textual strategies of fragmentation, anti-narrativity and non-linearity. This textualist approach of fragmentation and aporia derives from its proximity to the psychic state of the sufferers recalling their traumatic memories, which itself was greatly affected by the notion of memory.

However, trauma can also be the continuing and cumulative everyday experience of racism and institutional oppression. It can never become a history unless the sufferer leaves the culture that implements it and is thereby able to gain an un-racialised, un-oppressed new identity, or until the world makes an indisputably definitive break with the colonial histories. Neither personal nor collective history can become trauma; it is obsolete to attempt to understand trauma within the framework of memory in the current post-colonial multicultural world. The unknowability and irrepresentability of trauma should be reconsidered within the opacity that Édouard Gilssant advocates. It is about the irreducibility of difference; the inclusiveness of different realities and life experiences, to be told or decided not to be told as a choice, including of trauma.

Yellow Trauma attempts to diversify this exclusive trauma aesthetic conceived within a framework delineated by limited examples of human experience in order to create one true to the artist’s own. It draws on references outside the traditional field of trauma research and embodies the artist’s own lived experience through these discrete modes of cognition – the audio, visual and text – thematising her racialised and gendered identity as an Asian woman. The tripartite mode of the embodiment, for instance, evokes silence as the silenced state of the oppressed and disempowered, politicises gaze as the politics and a hidden location of power, and aestheticizes the optical recognition of colour to a racialised colour scheme.

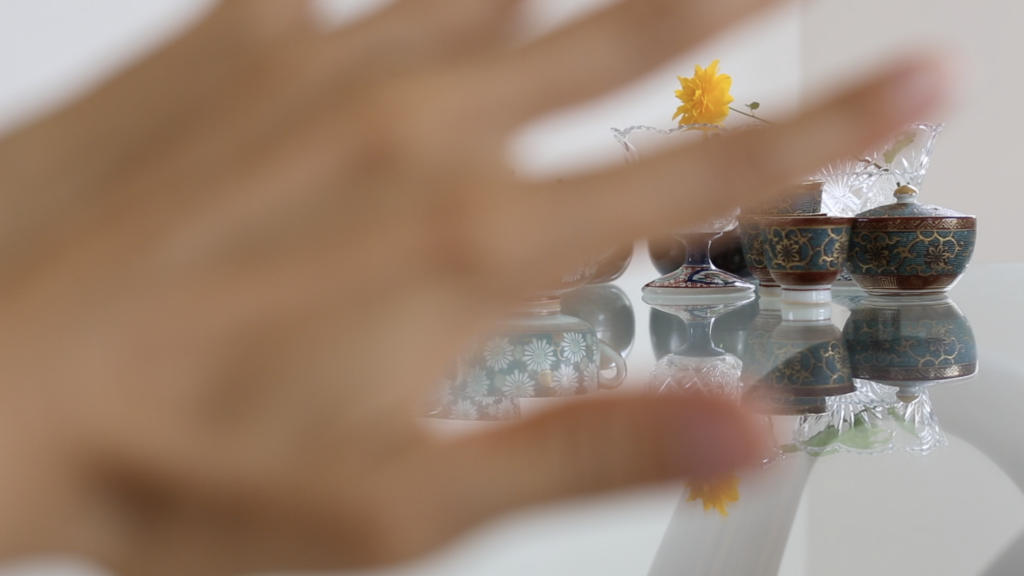

In the audio-visual work Yellow Adornment (1), with the artist’s own flesh exposed to its eye, the camera is employed as an apparatus of objectification, dehumanising her flesh into a racialised skin of Asiatic femininity. Manifesting the politics of gaze through its lens, the camera captures the racialised skin of Asiatic femininity in a white space, both architecturally and in terms of exclusionary white sociopolitical hegemony. Realised within this poetic reconfiguration of the house as a sociopolitical and hegemonial space, the visual refinement connotes the subtlety of microaggression. The racialised yellow woman sews a dress with yellow fabric; an act of making her own skin out of the racialised skin.

The house as a space oscillates between one that accommodates the body as a shelter and one that segregates the body as a sociopolitical and hegemonial space. Likewise, the dress is built up within this accommodation–segregation oscillation from the yellow fabric. The dress renders a restoration of the racialised and gendered individual from the flattened identity of yellow skin. Being visualised between the contradictory meanings of accommodating and segregating, those spaces that surround and envelop bodies, namely the architecture and clothes, resonate with the precarious status of the marginalised, liminal and peripheral being in society.

Towards the moonlight

A bough runs

Apart like rivers

Under the moisture-laden sky

Kerria quivers

Body in eclipse

Muted and ornamented

Yellow adornment

Embroidered

The texture beyond the needle

A lapse of the past

Enshrouded

Ostracised

Lines of threads

The stories eclipsed

Forge leaflets and shoots

Florets and berries

The quivered inflorescence

Indifference

The memory recalled

In fluorescence

Yellow reminiscence

Remorseless arborescence

Antithetical to European Minimalism, which distinguished the White and men in the Modernist dichotomy of race and gender, yellow women are ornamental and insubstantial, and are objects. Making this point refers to Anne Anlin Cheng’s thesis on the invention of race in European Modernist material–aesthetic productions of the colonial era of the late nineteenth century. The mask represents the European Modernists’ masculine, medical and hygienic view of the coronavirus and their commensurately feminising, medicalising and hygienicising gaze towards contemporary Asians as its signifier. The mask appears as femininity, skin, muteness and distance, representing an invisible, silenced and aesthetic being as the state of Asian women.

The noiseless being, her silence, must be experienced as silky on one’s own skin – this deranged identification of the self through the silence, discovered within the Modernist dichotomy and between the sensory faculties; the Self and the Other are utterly identical. With Yellow Adornment (1) embodying the aesthetic state of yellow women itself, the white cube of a gallery space is another sociopolitical and hegemonial space, in which she, the showcase, doubly appears as an adornment and as the state and status of the ghostly Self of Modernism that has been mirrored.

The lascivious ogle of the Self towards Otherness is expressed through the camera in the politics of gaze as well as in the text of Nectar, Skin Fallen like Fabric and The Quivered. Despite Theodor Adorno’s remark insinuating that the Holocaust enforces the hegemony of trauma; “It is barbaric to write a poem after Auschwitz”, one still writes poems and attempts to communicate with the rest of the world through one’s own words and one’s own aesthetics. With precise correspondence to the corporeal landscapes that the human body lives in with sheer actuality, poems continue to delineate acts of dehumanisation of any kind.

Skin fallen like fabric

Passed in the leer

Like glimmer

Lips hidden in public

Muted in the air

Like glitter

She is sentient

Lascivious aperture

Injurious rupture

Silky silence

Prevailed in public

Despite the pandemic

A micro respiration

In aggression

Breath

Hollow and yellow

Varnished into public

Skin fallen like fabric

Shade

Glimmered and glittered

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has altered lineage and genealogy. Yellow Trauma can be read from the perspectives both of Asians and of Orientalists, indicating the duality of the meaning. Such an irrevocable duality calls for empathy and understanding. The moments of fragility, loss, flux and change invoke a ghostly mirror, from which the Other looms to identify and disidentify the Self. We hear those callings, irrespective of whether we are enticed or reject them. Our action alters lineage and genealogy.

Yellow Adornment (1), 2024

Nectar, 2024

The Quivered, 2024

Skin Fallen Like Fabric, 2024